Electric vehicles are rapidly transforming transportation, offering a promising path toward a cleaner and more sustainable future. Yet, behind the scenes, one challenge continues to limit their potential: battery degradation. The lithium-ion batteries that power most EVs wear down with time and use but new research is opening the door to a groundbreaking solution—EV batteries that could last for up to one million kilometers without the need for replacement.

This advancement stems from a reimagining of the battery’s internal structure rather than an overhaul of its chemistry. By altering how the materials inside a battery are engineered, scientists may have found a way to vastly extend its usable life while maintaining, or even enhancing, performance.

At the core of lithium-ion batteries are nickel-based cathodes. These cathodes store and release lithium ions during every charging cycle. Traditionally, they are made of many small crystals packed together. Over time, the continual movement of ions causes these crystals to crack and fragment, weakening the material and making the battery less capable of holding a charge.

Increasing the energy density of a battery often achieved by using more nickel adds its own set of problems. While it allows vehicles to travel farther on a single charge, it also makes the cathode more prone to damage. When too much lithium exits the structure during discharge, the material collapses unevenly, creating tiny cracks that reduce the number of cycles a battery can survive. This degradation directly affects the lifespan and efficiency of electric vehicles.

In a pivotal development, researchers at Pohang University of Science & Technology in South Korea, led by Professor Kyu-Young Park, have focused on reengineering the structure of cathodes. Rather than relying on many small crystals, their approach centers around forming the cathode as a single large crystal. This design has fewer internal boundaries and is much more resistant to the kinds of stress that cause cracking.

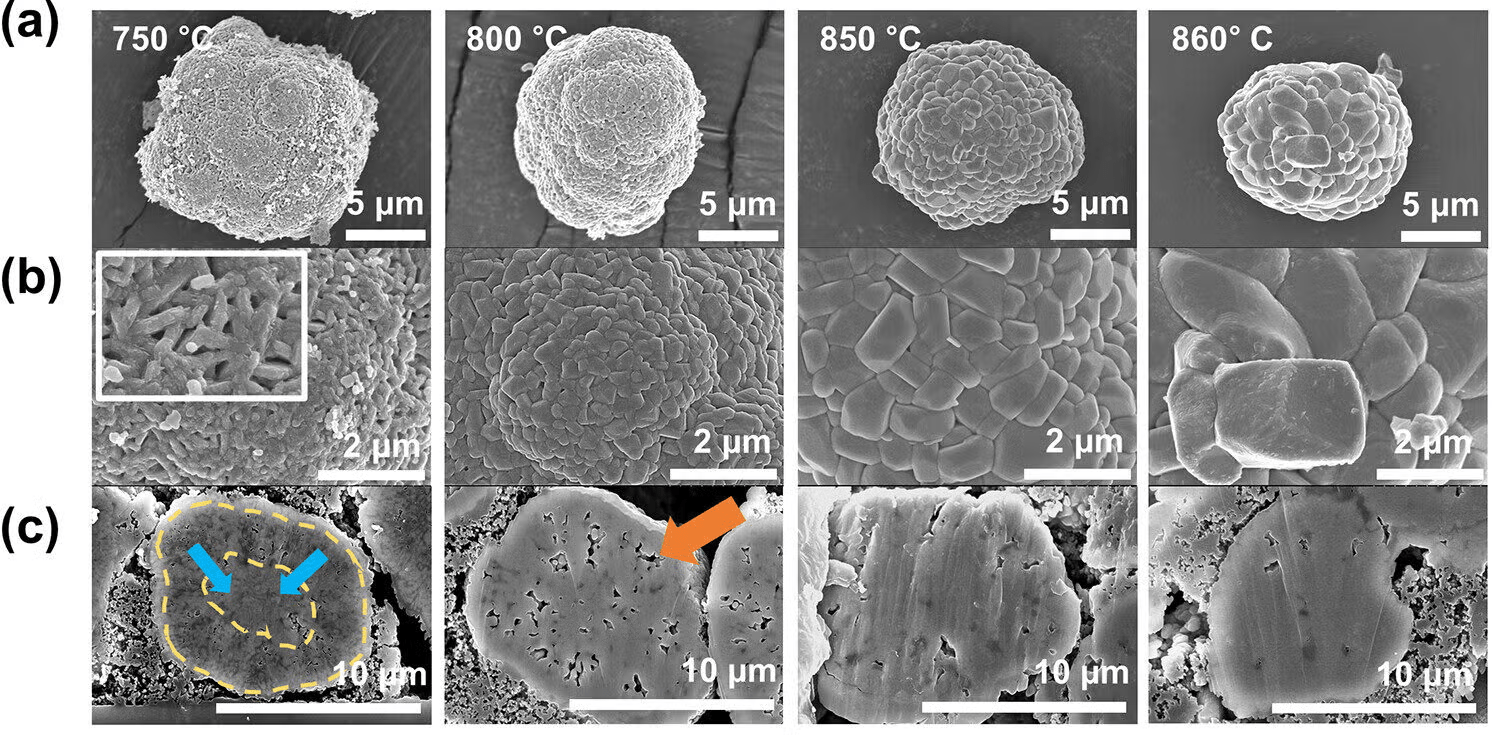

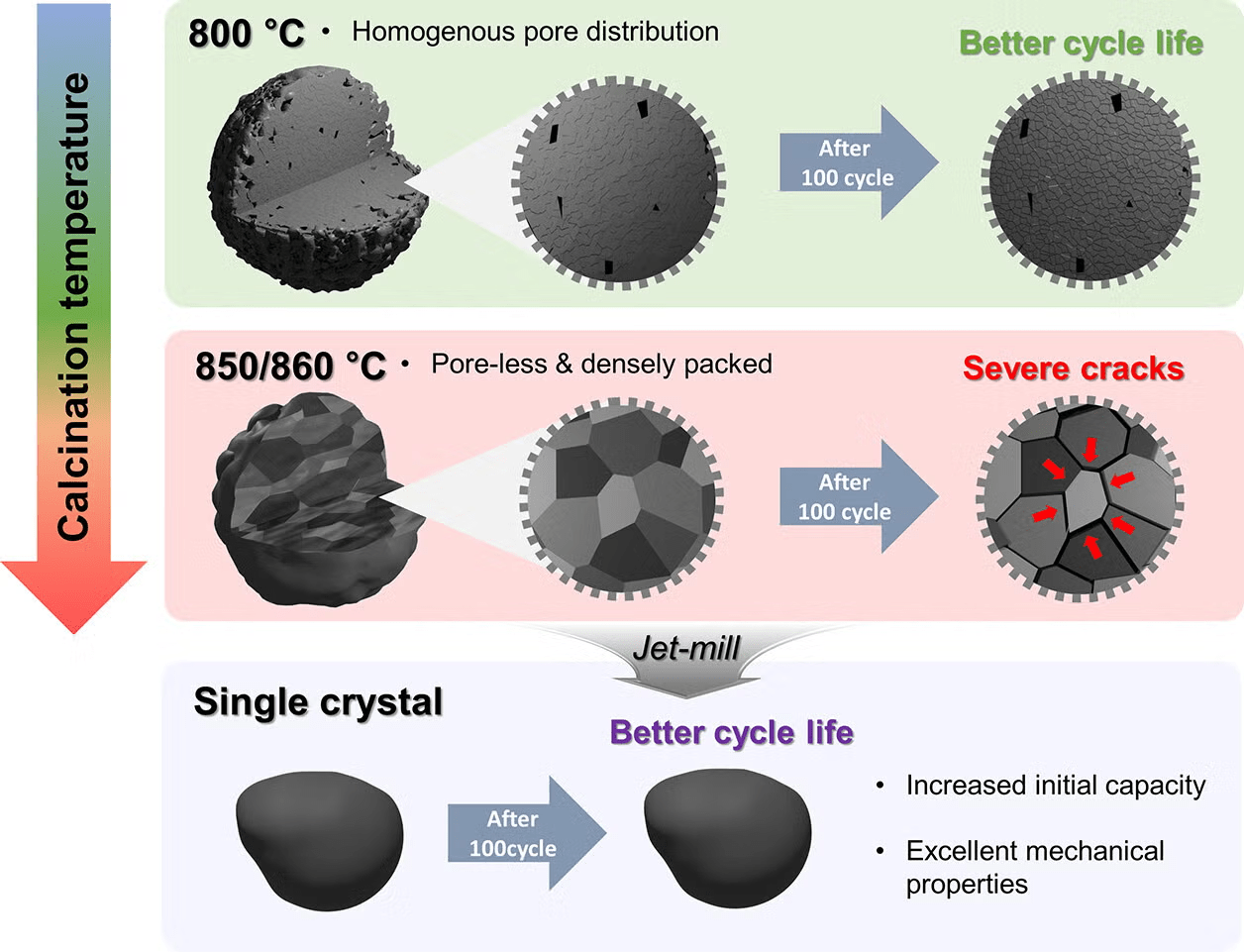

To create these single-crystal cathodes, the research team experimented with heating the materials at different temperatures. They found that above 850 °C, the nickel-based cathodes underwent a transformation. Tiny grains merged into larger, denser structures in a process known as densification. This process removed the small air pockets that typically weaken the cathode and created a structure much less vulnerable to wear and tear.

The key difference lies in how the materials respond to stress. While polycrystalline cathodes made at high temperatures become overly dense and brittle, single-crystal cathodes withstand the same conditions without cracking. With no grain boundaries to fail, they maintain structural integrity far longer, offering a solution to the durability problem that has long plagued EV batteries.

Historically, engineers have faced a difficult trade-off between battery power and lifespan. High-energy batteries tend to degrade faster, while more durable designs often sacrifice performance. This new research suggests that it may finally be possible to have both.

By focusing on the microstructure of the cathode specifically the size and distribution of grains and pores scientists can design materials that absorb mechanical stress more evenly. Below 850 °C, the material retains small, evenly spaced pores that help cushion stress. Above that threshold, the behavior of the material changes dramatically, but single-crystal cathodes formed at these higher temperatures show superior stability and longevity.

Professor Park’s team has demonstrated that battery life is not just about chemical composition; it’s also about how the materials are structured. Their findings could shift the entire landscape of battery development, giving manufacturers a new route to stronger, longer-lasting energy storage without sacrificing the power drivers expect from EVs.

While designing better batteries is essential, another major question looms: what happens when they finally wear out? The rise of electric vehicles brings with it a looming waste problem. If not properly handled, used batteries could cause serious environmental damage. Lithium-ion cells contain heavy metals like cobalt, nickel, and manganese, which can contaminate soil and water if they leak into the environment.

Disposing of these batteries responsibly is complex and expensive. Recycling them requires energy-intensive processes and specialized equipment. Nevertheless, scientists are developing better recycling techniques. Hydrometallurgy, for instance, uses chemical solutions to dissolve and recover valuable metals, while direct recycling seeks to restore usable parts of the battery—like the cathode—without breaking them down entirely.

Another avenue being explored is repurposing. Many EV batteries still retain up to 80 percent of their original storage capacity even after they’re no longer viable for vehicle use. These batteries can be reused in less demanding environments, such as storing energy from wind or solar farms. Giving them a second life can reduce waste and add value to what would otherwise be discarded.

The development of alternative battery chemistries is also underway. Solid-state batteries and sodium-ion batteries are being explored as safer, more recyclable options that could ease the environmental impact of widespread EV adoption.

The work doesn’t stop at the lab bench. Governments around the world are beginning to implement regulations that require manufacturers to take greater responsibility for battery disposal. Some policies require battery producers to accept and recycle spent units, while others provide incentives for creating closed-loop recycling systems. These initiatives, combined with research breakthroughs, are driving progress toward a more sustainable EV future.