NASA’s Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) mission encountered a small space rock called Dimorphos in late September. The impact was that it reduced 32 minutes off Dimorphos’ orbit around its larger companion, Didymos.

“DART has been a tremendous success,” Tom Stadtler, program scientist for the DART mission, said during a news conference held on Thursday (Dec. 15) in conjunction with the meeting. “I’ve seen these results, I know that they’re extremely cool.” NASA also published the early results from the mission here.

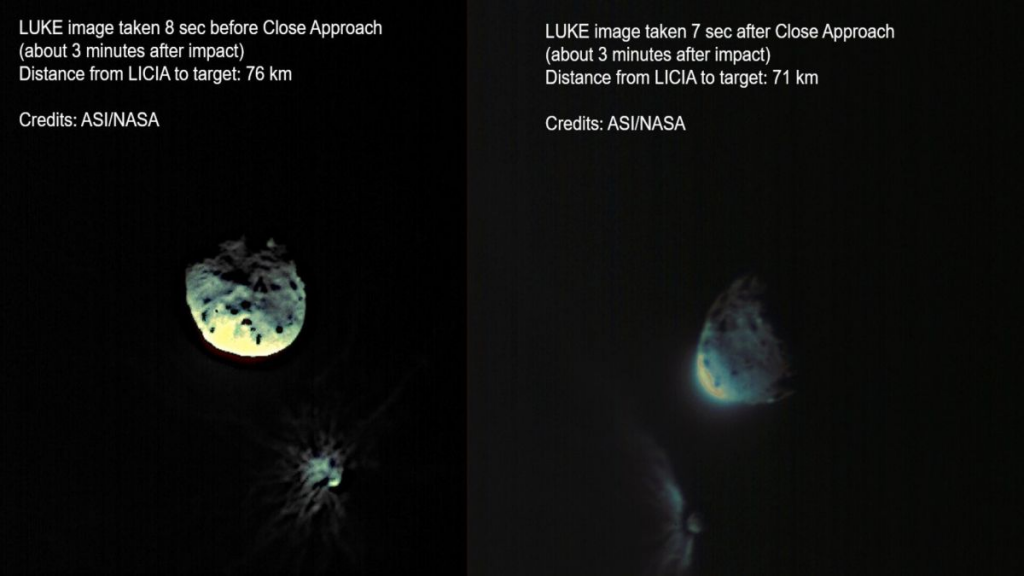

Scientists were able to witness it through the Light Italian Cubesat for Imaging of Asteroids (LICIACube). It has two cameras and was launched 15 days before DART’s impact.

“The images were indeed impressive,” Alessandro Rossi, LICIACube science team member and a scientist at the Instituto di Fisica Applicata Nella Carrara in Italy, said during the news conference. “We didn’t expect some of the features that we see.”

The scientists were able to compare Dimorphos and Didymos and tell they were quite similar.

“We have a vision of the ejecta plume from close by, we have a vision from the ground, we have the vision from Hubble Space Telescope, from the James Webb Space Telescope,” Rossi said. “So we have a lot of different geometries to compare with, and this is allowing us to clearly characterize the ejecta plume from many points of view.”

They have also estimated that at least 2.2 million pounds (1 million kilograms), and possibly as much as 22 million pounds (10 million kg) flew off the asteroid.

“We’re talking about a tiny, tiny fraction,” Andy Rivkin, a planetary scientist at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory and co-lead of DART, said in the news conference.

Scientists use a crucial number, called the “momentum transfer factor” or beta, to describe how effective an asteroid impact is. A beta of 1 is when there is no impact.

The beta factor of DART’s impact at 3.6. That value means that the asteroid picked up more than triple the momentum that it would have in a clean impact.

“This is very good news for the kinetic impact technique,” Andy Cheng, DART investigation team lead at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory, said during the news conference. “At least in the case of DART, the kinetic impact on the target was really efficient at changing the orbit of the target.”

“Where we’re trying to get is to have that ability to observe an asteroid, both from the ground or maybe with a reconnaissance mission, and infer what the response will be if we do deploy a kinetic impactor against it,” Stadtler said.

“From here, now, we actually get to get to our dream list, where we can start to think about the really complicated dynamical effects that were predicted, that we weren’t sure that we would be able to observe because we’d never done this before,” Thomas said. “We are looking forward to more observations that are going to allow us to study things in great detail, and I think that’s a really exciting place to be.”