It’s absurd to imagine cockroaches and humans ever becoming companions. However, some of their less desirable characteristics, such as their ability to squeeze through microscopic crevices and thrive in nearly any environment, made them the bug of choice for rescue operations.

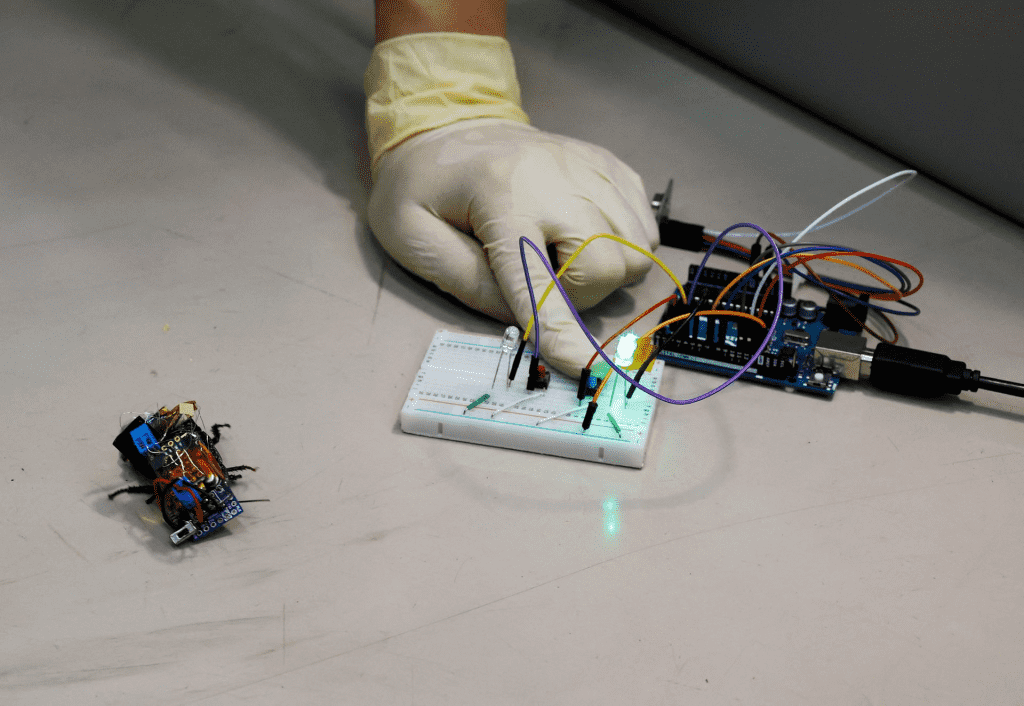

A cyborg cockroach is a biological bug that a human operator can remotely control. An innovation of this type may be utilised to investigate dangerous regions, monitor the environment, and perhaps identify persons trapped beneath the rubble.

However, to make this a reality, the capacity to remotely direct the insect over an extended time is required. In addition, wireless leg control and an onboard battery are needed to operate the device. However, the first obstacle has already been overcome. An international team led by researchers from the Japanese RIKEN Cluster for Pioneering Research (CPR) has just developed a device that recharges the battery using solar power.

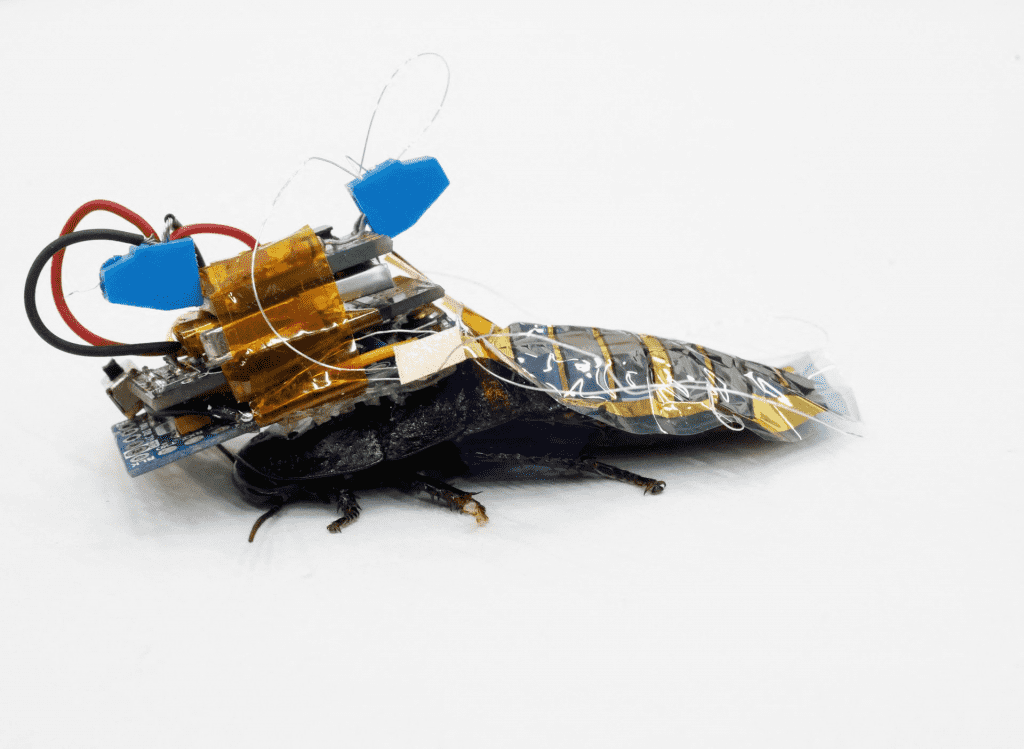

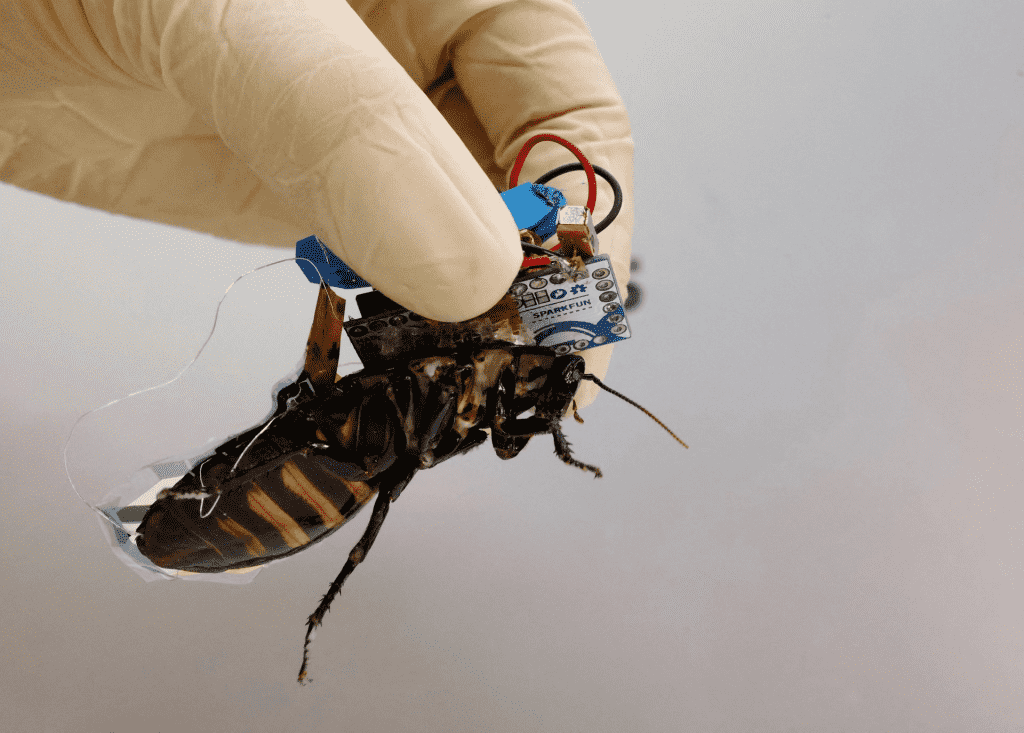

The team, headed by Kenjiro Fukuda, created a customised backpack that is ultra-thin (0.004 mm). These flexible organic solar cell modules stick to the insect’s body without interfering with its normal motions. This allows remote-controlled cockroaches to be sent on search missions in inaccessible or dangerous areas without returning to docking stations for recharging. The most urgent use of this technology is in rescue efforts, such as building collapses when persons buried beneath the rubble cannot be reached.

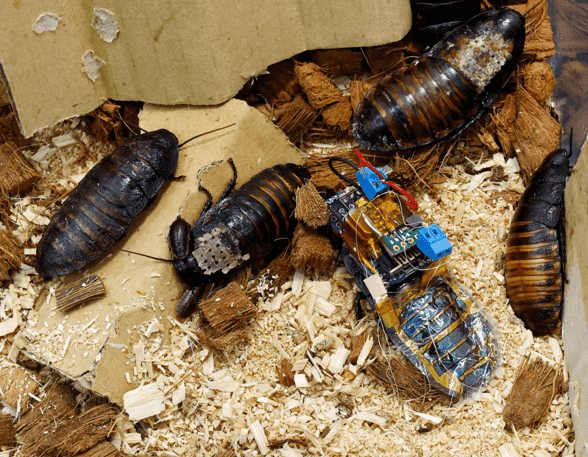

According to Nature, the Madagascar hissing cockroach species was employed in the study because of their relatively big size (5-7 cm), which provides an adequate surface area to incorporate the tiny solar cell and control gear. Since this species cannot fly, it is easy to locate. According to Fukuda, the insect does not have to carry the extra baggage forever. “After the mission, we can remove the device, and the insect may resume a normal life.”

Are we getting any closer to being able to control other animals? According to Fukuda, this is dependent on whether it experiences pain. Since insects do not experience pain, “there is no need for ethical approval.” However, when it comes to other living creatures, such as mammals, the use of this sort of technology is limited.

“That would be a problem because they do feel pain,” said Fukuda. But this battery-recharging mechanism can also be used with other cyborg insects, such as bees.

Nonetheless, the circuit management system must be improved so that the insect may transition between “recharge” and “mission” mode as quickly as possible.

“We need to guide the insect to sunlight before the battery runs out. Then, after recharging, we need to switch back to mission mode so that it restarts the rescue route. That’s the problem we’re tackling in the next phase of research,” said Fukuda, who anticipates being able to deploy cockroaches on a mission in three to five years.