In a move reminiscent of a science fiction narrative, a groundbreaking development emerged from the laboratories in China: the birth of a gene-edited monkey with striking green eyes. This significant breakthrough marked the world’s first successful live birth of a chimeric non-human primate.

The procedure was as intricate as it was controversial. Scientists injected seven-day-old monkey embryo stem cells into an unrelated four-to-five-day embryo of the same species, which was then placed within a female monkey. The outcome was nothing short of astonishing—a fully formed male monkey, where the introduced genetic material accounted for a substantial percentage of the newborn’s tissue composition.

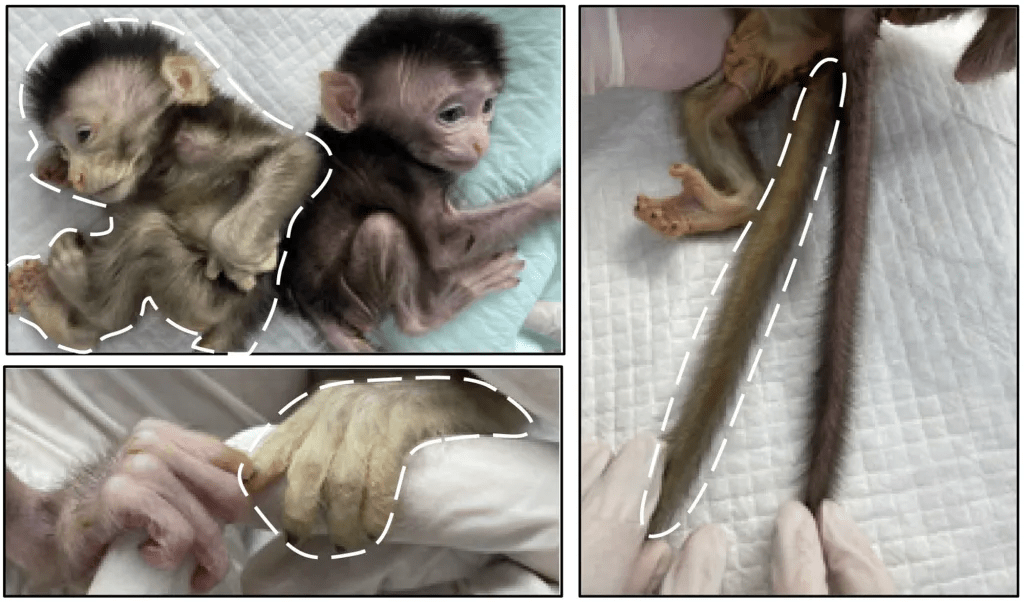

The injected stem cells took on an impressive role in the monkey’s development, forming a staggering 92% of its brain tissue and contributing to 67% of its overall makeup. The use of green fluorescent protein allowed scientists to track the pluripotent cells, which differentiated into various types necessary for the animal’s formation. After birth, the presence of these cells was observed in 26 different types of tissue, ranging from 21% to 92% in contribution.

While this innovation presented promising possibilities for generating more precise monkey models to study neurological diseases and biomedical research, it also ignited ethical debates. The short life of the gene-edited monkey, living for only 10 days before succumbing to respiratory failure and hypothermia, highlighted the challenges and risks associated with such advanced genetic manipulation.

The creation of chimeric organisms for human use raises ethical concerns, yet it also holds potential for advancing medical research, particularly in understanding human diseases and potentially growing organs for transplant. This approach could also aid in the conservation of critically endangered species facing extinction.

The close evolutionary relationship between humans and monkeys makes the latter a valuable resource for deeper insights into human physiology and diseases, setting them apart from other animal models, such as mice, which may not faithfully represent various human conditions due to physiological differences.

As this pioneering research unveils the potential for studying diseases and organ development, it simultaneously raises profound questions about the ethical implications and responsible use of such advancements in the realm of science and medicine.