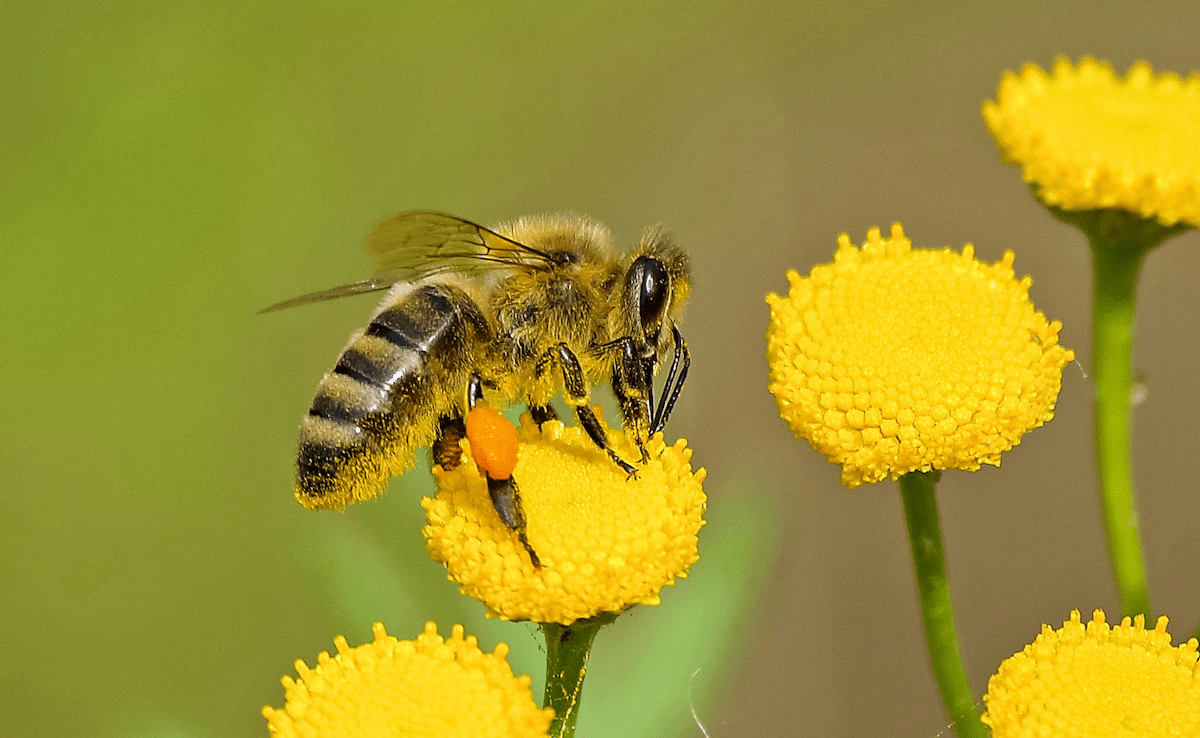

Nature’s designs often humble even our most advanced engineering. Take the honeybee: it can carry nectar loads nearly equal to its body weight, flies streamlined with tucked legs to reduce drag, and travels up to 5 kilometers without needing a break. For years, such feats have been unmatched by human machines—until now.

At the Beijing Institute of Technology, a research team led by Professor Zhao Jieliang has unveiled what may be a defining leap in insect-based robotics: the world’s lightest insect brain controller. Weighing just 74 milligrams lighter than the nectar sacks bees haul daily, this device transforms a living bee into a remotely guided “cyborg,” capable of responding to flight commands like turning, advancing, or retreating.

The device, described in a peer-reviewed paper published June 11 in the Chinese Journal of Mechanical Engineering, connects to the bee’s brain via three microscopic needles. Through precisely timed electronic pulses, it can override the insect’s instincts. In nine out of ten tests, the bee obeyed the commands.

Zhao’s team envisions these cyborg insects performing high-risk missions. With natural agility, camouflage, and adaptability, the modified bees could operate in complex terrains where machines would struggle, scouting disaster zones for survivors, slipping unnoticed through urban battlefields, or aiding in narcotics interdiction.

“Insect-based robots inherit the superior mobility, camouflage capabilities, and environmental adaptability of their biological hosts,” Zhao and his colleagues wrote. Compared to artificial drones, which require visible propulsion systems and constant recharging, these biological hybrids offer extended endurance and high stealth potential, particularly useful in covert operations and search-and-rescue scenarios.

This innovation has leapfrogged the previous lightest cyborg controller, developed in Singapore, which was more than three times heavier and limited to commanding beetles and cockroaches. Those insects moved slowly and fatigued rapidly, limiting their usefulness in the field.

The breakthrough came through ultrathin design: the team printed electronic circuits on a polymer film as thin and flexible as an insect wing. Despite its delicate appearance, the film hosts several integrated chips and includes an infrared receiver to accept remote commands.

Zhao’s team also studied movement mechanics in both bees and cockroaches. Through nine different pulse settings, they mapped specific motion responses—such as turning or straight-line crawling—to different signal combinations. Roaches could be made to walk straight with minimal deviation, and bees banked midair with remarkable precision.

Yet the cyborg system is not without flaws. Power remains a primary obstacle. Bees still require wired electricity because current battery technology cannot support untethered flight. A sufficiently long-lasting battery would weigh 600 milligrams—far too heavy for a bee to carry. Additionally, insect behavior remains somewhat inconsistent: the same signal can trigger different movements in different individuals. Bee legs and abdomens also appear resistant to command inputs, suggesting limitations in full-body control.

The researchers acknowledge these challenges. In their paper, they noted plans to enhance the repeatability of behavioral control by refining their electrical signals and stimulation methods. They also aim to expand the functionality of the control backpack to give these cyborg insects a richer perception of their environment, crucial for navigating real-world missions like reconnaissance, detection, or disaster response.

The race to dominate cyborg insect technology is heating up. While the U.S. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) once led the field, and Japan maintained a steady presence, China now appears to be outpacing both. With robust state funding and a vast electronics manufacturing ecosystem, Chinese researchers are not just keeping up—they’re setting new records.

From “rent-a-bee” pollination services to battlefield surveillance, insect cyborgs once seemed like speculative science fiction. But the Beijing Institute of Technology’s microcontroller pushes the concept into a tangible, high-tech reality, one that may reshape how we think about machines, biology, and the blurred line between them.