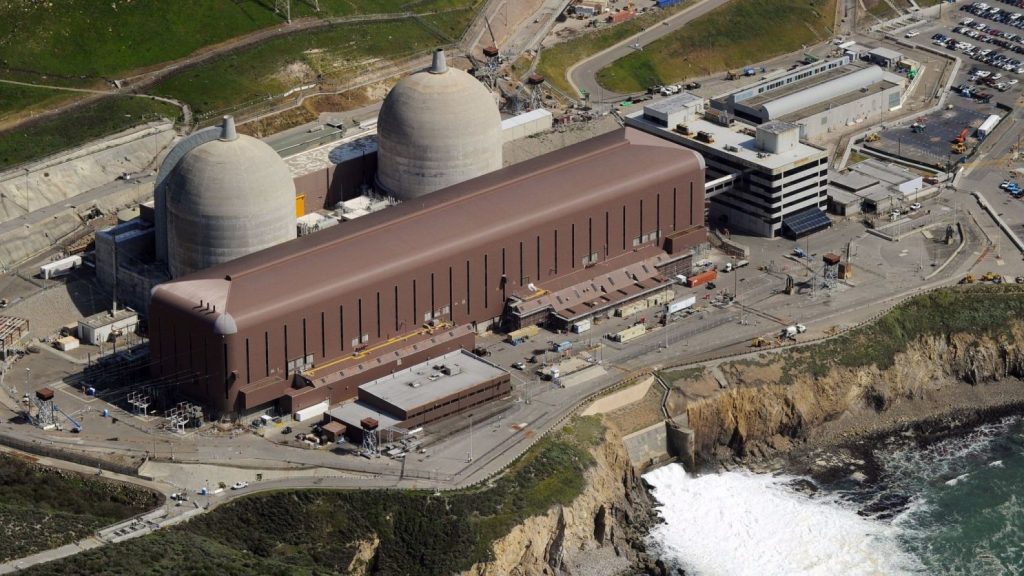

California’s last nuclear facility, the 2.2 GW Diablo Canyon nuclear power plant, approaches its projected retirement date, and several energy experts are concerned that the state has not adequately prepared for what comes next.

The Diablo Canyon facility, located on California’s Central Coast, generates around 18,000 GWh of power per year, accounting for nearly 10% of the state’s total energy supply. In 2018, authorities granted Pacific Gas & Electric (PG&E) permission to close the plant’s two reactors when their licenses expire in 2024 and 2025. However, as those deadlines approach, experts are concerned about what it would entail for California’s reliability and greenhouse gas (GHG) emission targets.

The plant is California’s largest power source, and unlike solar panels and wind turbines, Diablo Canyon can generate electricity 24 hours a day, seven days a week — an essential feature for a state that experienced brief power outages last summer.

It is usual for nuclear shutdowns to be followed by increasing pollution as fossil-fueled power facilities start more frequently.

California’s carbon pollution increased by 2% after the San Onofre generating facility in San Diego County malfunctioned, eventually leading to its permanent closure. Of course, that wasn’t the only reason emissions increased, but it was almost probably a role.

Similarly, the share of New York state’s electricity generated by natural gas, a fossil fuel, increased by 4% points after one of the two reactors at the Indian Point nuclear station shuttered last year. Last month, the other reactor produced its final electrons.

It shouldn’t have to be this way, and Diablo Canyon is an example of retiring a nuclear reactor without worsening the climate issue. However, critics assert that Gov. Gavin Newsom’s Public Utilities Department is ineffective.

“Diablo’s retirement is going to increase greenhouse gas emissions. And their planning is not doing anything to prevent that,” said Mark Specht, an energy analyst at the Union of Concerned Scientists. “We should have figured this out by now.”

California is a staunch supporter of clean energy. The state-approved legislation in 2018 is forcing us to use 100% zero-carbon electricity by 2045. But why is it closing its only clean energy source? The explanations differ depending on which stakeholder you question. California’s fervent anti-nuclear agenda is a significant factor in the state’s last functioning nuclear power plant’s closing.

“The politics against nuclear power in California are more powerful and organized than the politics in favour of a climate policy,” David Victor, professor of innovation and public policy at the School of Global Policy and Strategy at UC San Diego, told CNBC.

These safety concerns are taking place in the context of changing attitudes against nuclear energy in the United States.

“Since Three Mile Island and then Chernobyl, there has been a political swing against nuclear—since the late 1970s,” Victor told CNBC. “Analysts call this ‘dread risk’ — a risk that some people assign to a technology merely because it exists. When people have a ‘dread’ mental risk model, it doesn’t really matter what kind of objective analysis shows safety level. People fear it.”

A system of loud sirens known as the Early Warning System Sirens is in place in San Luis Obispo County to alert nearby residents if something goes wrong at the nuclear power plant. Unfortunately, those sirens, when tested, are terrifying to hear.

“That is a very clear reminder that we are living in the midst of a potentially incredibly dangerous nuclear power plant in which we will bear the burden of that nuclear waste for the rest of our lives,” Heidi Harmon, the most recent mayor of San Luis Obispo says.

Harmon also has reservations about PG&E because of its shady past. In 2019, the firm agreed to a $13.5 billion settlement to resolve legal claims that its equipment was responsible for several fires around the state. In August 2020, it pled guilty to 84 charges of involuntary manslaughter resulting from a fire it failed to fix.

“I know that PG&E does its level best to create safety at that plant,” Harmon told CNBC. “But we also see across the state, the lack of responsibility, and that has led to people’s deaths in other areas, especially with lines and fires,” she said.

However, PG&E insists that the facility is not shutting down due to safety concerns.

The Long Term Seismic Program, a group of geoscience professionals at the utility, with independent seismic experts, ensure the facility’s safety, according to Suzanne Hosn, a spokesman for PG&E.

“The seismic region around Diablo Canyon is one of the most studied and understood areas in the nation,” Hosn said. “The NRC’s oversight includes the ongoing assessment of Diablo Canyon’s seismic design and the potential strength of nearby faults. The NRC continues to find the plant remains seismically safe.”

A retired technical executive who worked at the plant during its operation also backed its safety.

“The Diablo Canyon Nuclear Power Plant is an incredible marvel of technology, and has provided clean, affordable and reliable power to Californians for almost four decades with the capability to do it for another four decades,” Ed Halpin, who was the Chief Nuclear Officer of PG&E from 2012 until he retired in 2017, told CNBC.

“Diablo can run for 80 years,” Halpin told CNBC. “Its life is being cut short by at least 20 years and with a second license extension 40 years, or four decades.”

When PG&E begun the process in 2016, it gave somewhat different reasoning for shutting Diablo Canyon.

One explanation, according to the 2016 legal documents, is that an increasing number of California residents purchasing electricity through community choice aggregators (CCA), which are local energy purchasing groups. Many of these organisations refuse to buy nuclear power.

Meanwhile, CCAs have been more interested in other forms of renewable energy instead of investing in nuclear energy.

“As part of its energy portfolio in addition to solar and wind, CCCE is contracting for two baseload (available 24/7) geothermal projects and large scale battery storage, which makes abundant daytime renewable energy dispatchable (available) during the peak evening hours,” said the organization’s CEO, Tom Habashi.

Having said that, the political view of the general community can not be ignored.

“In a regulated utility, the most important relationship you have is with your regulator. And so it’s the way the politics gets expressed,” Victor told CNBC. “It’s not like Facebook, where the company has protesters on the street, people are angry at it, but then it just continues doing what it was doing because it’s got shareholders and it’s making a ton of money. These are highly regulated firms. And so, they’re much more exposed to politics of the state than you would think of as a normal firm.”

The percentage of renewables is increasing manifold with each passing day. California is all set to garner most of its energy from the sunshine. In the backdrop of this inevitable change, nuclear power and its maintenance will become a financial handicap over the years.

The initial plan was to decommission the nuclear plant in 2016, after which it would continue working till 2025. After the shutdown in 2025, the fuels will be removed from the site in a couple of years. It takes a decade, in general, to shut down a nuclear plant.

“For a plant that has been operational, deconstruction can’t really begin until the fuel is removed from the reactor and the pools, which takes a couple of years at least,” Victor told CNBC. Only then can deconstruction begin.

“Dismantling a nuclear plant safely is almost as hard and as expensive as building one because the plant was designed to be indestructible,” he said.

All of these factors are in conjunction with the political climate that is driven by renewables. Victor stated that an expensive repair would have been mandatory to renew the plant’s operating license, he said.

“The situation of Diablo is in some sense more tragic because, in Diablo, you have a plant that’s operating well,” Victor said. “A lot of increasingly politically powerful groups in California believe that [addressing climate change] can be done mainly or exclusively with renewable power. And there’s no real place for nuclear in that kind of world.”

The pro-nuclear constituents are still trying to salvage Diablo.

“It’s frustrating. It’s something that I’ve spent well in excess of 10,000 hours on this project pro bono,” said Gene Nelson, a representative of Californians for Green Nuclear Power.

“But it’s so important to our future as a species — that’s why I’m making this investment. And we have other people that are making comparable investments of time, some at the legal level, and some in working on other policies,” Nelson said.

Victor said that renewables might sustain the state’s power demands, but some spheres are still not ventured upon.

“The problem in the grid is not just the total volume of electricity that matters. It’s exactly when the power is available, and whether the power can be turned on and off exactly as needed to keep the grid stabilized,” he told CNBC. “And there, we don’t know.”

“It might be expensive. It might be difficult. It might be that we miss our targets,” Victor told CNBC. “Nobody really knows.”

The point to ponder here is that will the state be able to import energy or not. Historically, the state has been intaking hydropower from the Pacific Northwest and Canada and other power sources from across the West.

“California will be increasing renewable energy every year from now on,” Jacobson told CNBC. “Given California’s ability to import from out of state, there should not be shortfalls during the buildout.”