“Men are from Mars, and women are from Venus” — have you heard that phrase before? While in the 21st century, this is mostly seen as a trope, scientists from Stanford have found that there may be some basis to why and how a particular sex does what they do, according to a new study published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences on February 19.

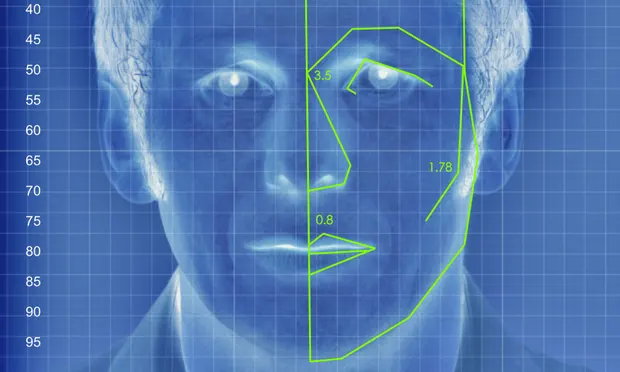

They have created a new artificial intelligence (AI) model that can accurately predict if brain scans are from a man or a woman over 90% of the time.

“A key motivation for this study is that sex plays a crucial role in human brain development, in aging, and in the manifestation of psychiatric and neurological disorders,” said Vinod Menon, Ph.D., professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences and director of the Stanford Cognitive and Systems Neuroscience Laboratory, in a press release.

Scientists have long debated the impact of a person’s sex on brain organization and function. Despite knowing that sex chromosomes influence hormone exposure, connecting sex to concrete brain differences has been challenging. Previous research found little consistency in brain structure or function between men and women. But, Menon and his team used advanced AI and large datasets to analyze brain scans. Their model outperformed previous methods, reliably distinguishing between male and female brains. This success suggests detectable sex differences exist in the brain, previously overlooked.

The model’s consistent performance across diverse datasets enhances the credibility of these findings. Inside the human brain, certain regions shine brighter to distinguish whether it belongs to a male or a female. The researchers identified certain ‘hotspots’ that were most useful for the model to determine the same.

The first is the default mode network, which helps us think about ourselves, and other areas like the striatum and limbic network, which are important for learning and how we react to rewards.

“Identifying consistent and replicable sex differences in the healthy adult brain is a critical step toward a deeper understanding of sex-specific vulnerabilities in psychiatric and neurological disorders,” added Menon.

Their AI model could analyze moving MRI scans. The team tested it on about 1,500 brain scans, and it could usually tell if the scan was from a man or a woman.

“This is a very strong piece of evidence that sex is a robust determinant of human brain organization,” Menon said.

“Our AI models have very broad applicability,” Menon said. “A researcher could use our models to look for brain differences linked to learning impairments or social functioning differences, for instance — aspects we are keen to understand better to aid individuals in adapting to and surmounting these challenges.” Then, they wondered if they could use another model to predict how well people would do on certain tasks based on brain features that differ between men and women.

They made separate models for men and women, and each one predicted cognitive performance better for their respective gender. This shows that differences in how brains work between men and women can affect how they behave.

While they used their model to look at sex differences, Menon says it can also be used to study how brain connections relate to any cognitive ability or behavior. They plan to share their model with other researchers.

The findings of the study were published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences on February 19.